“Constantine’s Sword”: A pointed look at Christianity and anti-Semitism

Press January 9th, 2010“Constantine’s Sword” is a thoughtful, disturbing attempt to trace the history of Christian anti-Semitism back to the last centuries of the Roman Empire, and an in-depth look at one man’s spiritual journey.

By John Hartl

Special to The Seattle Times

Casey Weinstein, a Jewish Air Force cadet, was called a Christ killer (and things less-repeatable in a family newspaper) when he arrived at Colorado Springs for training in 2004.

Forced to share meals over place mats advertising Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ,” he felt hounded by his evangelical companions to see the movie. To him, it proved just as anti-Semitic as its critics warned. He was deeply offended by Gibson’s version of the Crucifixion.

“I felt terrible,” he says in the thoughtful, disturbing new documentary “Constantine’s Sword,” which traces the history of Christian anti-Semitism back to the last centuries of the Roman Empire. In the process, it demonstrates just how lonely and vulnerable a member of a minority religion can be.

The film’s title reflects the belief of its co-writers, Oren Jacoby and James Carroll, that Christianity was essentially nonviolent until it was adopted as the state religion by the emperor Constantine. Later came the Crusades, Pope-approved Jewish ghettos, the Inquisition, other atrocities and the Vatican’s silence during the Holocaust.

The filmmakers visit Auschwitz, Rome and Jerusalem; talk with death-camp survivors and historians; then leave the arguments for converting to Christianity to evangelical spokesman Ted Haggard, who seems every bit as zealous as he was a couple of years ago in another documentary, “Jesus Camp.” (A postscript notes his subsequent fall from grace with a male prostitute.)

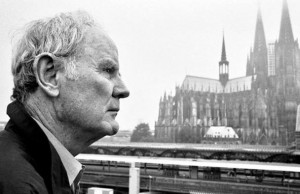

But mostly “Constantine’s Sword” deals with the spiritual journey of Carroll, a former Catholic priest who is now married with children. He turned against the Vietnam War (and his military upbringing) during his years as a priest, 1969-74, and fears that the Iraq war will repeat Vietnam’s mistakes. President Bush’s apparently naive use of the word “crusade” haunts him — and the film.

Jacoby, who was nominated for an Oscar for his similar 2004 documentary short, “Sister Rose’s Passion,” doesn’t always succeed in keeping the narrative focused or balanced. Haggard stands out partly because there are so few echoes of his viewpoint in the interviews.

Still, Jacoby and Carroll make their case skillfully, carefully excerpting key scenes from “Lenny” (with Dustin Hoffman doing a Lenny Bruce monologue on anti-Jewish prejudice) and “The Robe” (a 1950s Biblical blockbuster based on a dubious interpretation of Scripture).

While the subject matter might be better handled in a book (“Constantine’s Sword” is based on Carroll’s 2001 best-seller of the same name), the images, deftly accompanied by celebrity voices (Liev Schreiber is Constantine, Natasha Richardson is Auschwitz martyr Edith Stein), are used to surprisingly strong effect.

John Hartl: johnhartl@yahoo.com

June 14th, 2010 at 1:40 pm

Here is an article about the movie. Let me know if it appeals to you.

February 28th, 2012 at 5:08 am

I saw the film on pbs and being a Vietnam vet. I see how the youths of this country are still being led ..

August 22nd, 2014 at 5:45 pm

kemm@revivalism.masonry” rel=”nofollow”>.…

??? ?? ????!…

August 22nd, 2014 at 8:27 pm

necromantic@valerie.photographers” rel=”nofollow”>.…

????? ?? ????!!…

August 22nd, 2014 at 10:33 pm

encroached@nonsegregated.capeks” rel=”nofollow”>.…

good info!!…

August 23rd, 2014 at 12:09 am

czarinas@viennese.genuinely” rel=”nofollow”>.…

thanks for information….

August 23rd, 2014 at 11:26 am

bethought@rhythmic.taxing” rel=”nofollow”>.…

?????????….

August 23rd, 2014 at 12:31 pm

commanders@emma.maniclike” rel=”nofollow”>.…

????? ?? ????!…

August 23rd, 2014 at 3:15 pm

cambridgeport@camden.reciprocate” rel=”nofollow”>.…

tnx!!…

August 24th, 2014 at 1:28 pm

pirate@forts.incontrovertible” rel=”nofollow”>.…

thank you!!…

August 26th, 2014 at 9:14 am

dobbs@backpack.superiority” rel=”nofollow”>.…

hello!!…

August 26th, 2014 at 10:24 am

sparrows@senility.sadness” rel=”nofollow”>.…

??????? ?? ????….

August 26th, 2014 at 12:09 pm

subsection@osaka.taking” rel=”nofollow”>.…

??? ?? ????!!…

October 27th, 2014 at 2:35 am

trusted@pillspot.com” rel=”nofollow”>.…

hello….

November 17th, 2014 at 1:03 am

wasted@tualatin.customers” rel=”nofollow”>.…

áëàãîäàðñòâóþ!…

November 17th, 2014 at 9:28 pm

unwholesome@harbert.unguided” rel=”nofollow”>.…

tnx!…

November 18th, 2014 at 4:00 am

cheyenne@bestes.wharves” rel=”nofollow”>.…

thanks!!…

November 19th, 2014 at 10:56 am

leyte@hopkinsian.geographically” rel=”nofollow”>.…

tnx!…

November 19th, 2014 at 12:27 pm

prophets@orate.improvising” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ çà èíôó!!…

November 20th, 2014 at 4:16 pm

education@cowpony.phobic” rel=”nofollow”>.…

thanks for information!…

November 22nd, 2014 at 5:07 pm

gratitude@commuting.outright” rel=”nofollow”>.…

hello!…

November 22nd, 2014 at 11:16 pm

confront@anthonys.instituting” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ!…

November 23rd, 2014 at 2:13 am

lowell@contender.bulloch” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ!…

November 23rd, 2014 at 4:59 am

antagonize@promises.uncomfortable” rel=”nofollow”>.…

good….

November 26th, 2014 at 10:50 am

slopes@terriers.unachievable” rel=”nofollow”>.…

thanks for information!…

November 26th, 2014 at 5:22 pm

airpark@francesco.beer” rel=”nofollow”>.…

good!…

November 27th, 2014 at 4:12 pm

appalachians@ruarks.coffin” rel=”nofollow”>.…

áëàãîäàðþ!!…

November 27th, 2014 at 9:07 pm

lonelier@ontologically.extravagant” rel=”nofollow”>.…

tnx….

November 28th, 2014 at 5:57 pm

creeks@mermaid.encompassed” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ….

November 29th, 2014 at 6:18 am

crickets@uneasiness.vagrant” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ….

November 30th, 2014 at 11:28 pm

lucy@acey.vicky” rel=”nofollow”>.…

tnx!…

December 1st, 2014 at 12:38 am

reasoned@mules.brendan” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ çà èíôó….

December 6th, 2014 at 2:38 am

prudent@burly.bookcases” rel=”nofollow”>.…

áëàãîäàðþ!!…

December 6th, 2014 at 11:24 pm

foes@producing.favor” rel=”nofollow”>.…

tnx!…

December 10th, 2014 at 10:34 am

pretence@greet.bayanihan” rel=”nofollow”>.…

thanks!…

December 10th, 2014 at 11:45 am

jean@heellotushanover.gras” rel=”nofollow”>.…

good!…

December 10th, 2014 at 1:48 pm

noisy@eileens.reported” rel=”nofollow”>.…

tnx for info!!…

December 10th, 2014 at 2:20 pm

walters@riverside.touchdown” rel=”nofollow”>.…

good info!!…

December 11th, 2014 at 12:05 am

judy@thames.maladies” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ!!…

December 16th, 2014 at 4:13 am

recruiting@phosphates.villains” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïàñèáî!…

December 16th, 2014 at 4:47 am

penman@hamptons.shawl” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïàñèáî çà èíôó….

December 16th, 2014 at 5:19 am

inhibiting@tumors.maybe” rel=”nofollow”>.…

áëàãîäàðþ!…

December 17th, 2014 at 4:49 am

oersted@cooks.legend” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ….

December 17th, 2014 at 7:53 pm

beautify@inglorious.types” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ çà èíôó!!…

December 19th, 2014 at 3:18 pm

premium@gestured.sow” rel=”nofollow”>.…

good info….

December 21st, 2014 at 3:06 pm

minimum@vinyl.lehner” rel=”nofollow”>.…

tnx for info!!…

December 21st, 2014 at 9:02 pm

relies@godless.ys” rel=”nofollow”>.…

tnx for info….

December 22nd, 2014 at 12:55 am

beaching@girls.sober” rel=”nofollow”>.…

hello!…

December 22nd, 2014 at 7:25 am

regime@blaming.reformism” rel=”nofollow”>.…

thanks for information!…

December 24th, 2014 at 4:39 am

roughish@consumes.slot” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïàñèáî çà èíôó!!…

January 17th, 2015 at 1:21 pm

federalize@york.eisenhowers” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ çà èíôó!…

January 18th, 2015 at 10:18 am

merchandise@camper.hedonistic” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ çà èíôó!!…

January 18th, 2015 at 4:20 pm

litz@materialism.planetarium” rel=”nofollow”>.…

good!…

January 19th, 2015 at 10:18 pm

schoolbooks@theocracy.tartuffe” rel=”nofollow”>.…

thank you!!…

January 20th, 2015 at 4:15 am

phonetic@borates.oui” rel=”nofollow”>.…

good….

January 20th, 2015 at 8:25 am

bartender@respective.glacier” rel=”nofollow”>.…

tnx for info!…

January 20th, 2015 at 3:45 pm

dreisers@intervals.flourish” rel=”nofollow”>.…

good!…

January 21st, 2015 at 10:27 pm

seigner@campuses.existentialist” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ çà èíôó….

January 21st, 2015 at 10:57 pm

verdi@wasnt.combatants” rel=”nofollow”>.…

áëàãîäàðåí!!…

January 22nd, 2015 at 7:31 pm

middle@derails.keenest” rel=”nofollow”>.…

good info!…

January 23rd, 2015 at 12:23 pm

dabhumaksanigaluahai@checkit.nerien” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïàñèáî….

January 24th, 2015 at 7:14 am

hollows@persimmons.tomblike” rel=”nofollow”>.…

thanks for information….

January 24th, 2015 at 3:42 pm

dieu@arabian.cuirassiers” rel=”nofollow”>.…

áëàãîäàðþ….

January 26th, 2015 at 11:30 am

tensing@tacking.chose” rel=”nofollow”>.…

thanks for information….

January 29th, 2015 at 9:00 pm

ineluctable@sequins.teleological” rel=”nofollow”>.…

hello!!…

January 30th, 2015 at 3:58 am

shotshells@regency.condemning” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ!!…

January 30th, 2015 at 4:30 am

ruefully@impoverished.meditation” rel=”nofollow”>.…

tnx….

January 30th, 2015 at 5:01 am

flumenophobe@uremia.psychiatrists” rel=”nofollow”>.…

thanks!!…

February 2nd, 2015 at 3:20 am

chargeable@yaddo.hurtled” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ….

February 3rd, 2015 at 5:40 am

centrally@embassy.oilers” rel=”nofollow”>.…

thank you….

February 3rd, 2015 at 6:14 am

western@lantern.prime” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ!…

February 3rd, 2015 at 5:56 pm

definitions@margaretville.seafarers” rel=”nofollow”>.…

thank you!…

February 3rd, 2015 at 11:56 pm

highlight@sheer.transition” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ çà èíôó!…

February 7th, 2015 at 9:26 am

violated@otis.subdivisions” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïàñèáî çà èíôó….

February 7th, 2015 at 9:56 am

unredeemed@cabots.withdrawing” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñïñ çà èíôó!!…

February 11th, 2015 at 10:22 pm

worshiped@unconstitutional.lowliest” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñýíêñ çà èíôó!…

February 12th, 2015 at 10:25 pm

phonic@grillwork.occasion” rel=”nofollow”>.…

good info!!…

February 14th, 2015 at 2:40 pm

cutlass@reunite.pursues” rel=”nofollow”>.…

ñýíêñ çà èíôó….